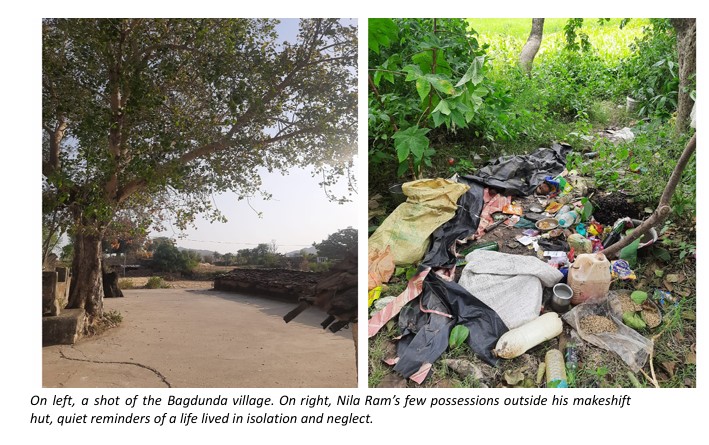

When we first met 65-year-old Nila Ram in Bagdunda (a village in which we run one of our Amrit Clinics), he had already spent more than three decades living with Schizophrenia, without ever receiving formal medical care. Years of illness and neglect had left him withdrawn and disconnected. With no family of his own and no one to look after him, he lived alone in a makeshift hut in the fields, on the outskirts of the village. Over time, the community had grown used to his presence – quiet, distant, and wandering. For most people around him, his condition was not seen as an illness but as a divine punishment, something beyond the reach of medicine.

Yet, we found hope in his sister, Bhamri Bai, a 60-year-old who herself lives with hypertension and depressive symptoms. She not only made efforts to understand that mental illness can be treated but also volunteered to support us in his care. Despite facing hostility from her family and community, she ensures that her brother takes his medicine every day. In caring for him, she has found renewed purpose and a quiet strength that continues to inspire our team.

At BHS, we have come to understand that access to mental health care is not just about the physical availability of doctors or medicines. It also depends on the readiness and confidence of individuals, families, and communities, many of whom have long been on the peripheries of society.

Among the communities we work with, mental illness, especially severe forms, is often seen as a divine affliction or a result of jadu tona (black magic). Seeking help from the medical system can feel inappropriate, or even undesirable. We knew, therefore, that to make care truly accessible, we would have to meet people halfway, in their own communities, where they feel most comfortable, while also bringing in the scientific knowledge and resources that support recovery.

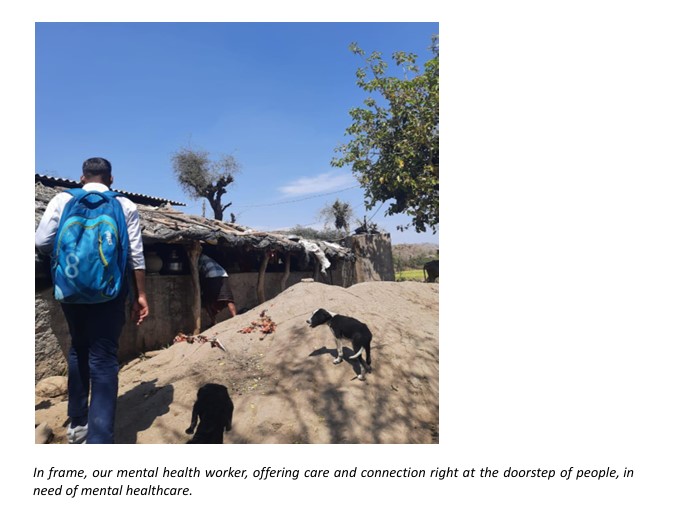

Our community-based mental health work is grounded in the principle of making care not just accessible, but contextual and relevant. We do this with the help of our mental health workers, people who come from the same villages, share the same language, and understand the rhythms of community life. They gently challenge long-held beliefs, build trust through everyday conversations, and accompany families on their journey toward recovery. When this deep local understanding is paired with structured training and regular supervision, it leads to remarkable transformations.

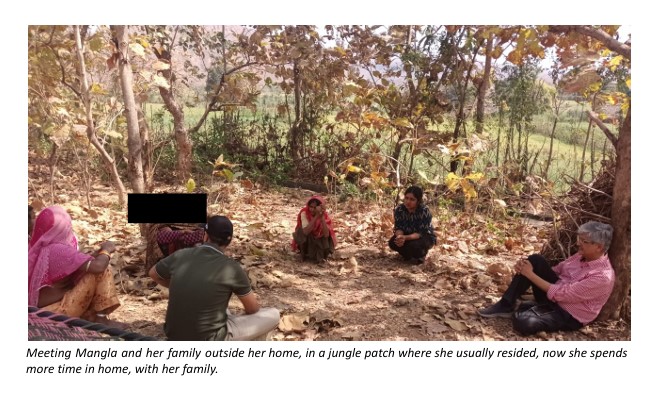

One such story is that of Mangla, a woman who had lived outside her home for years due to her illness. Through continuous engagement, our mental health worker helped her family understand her condition and encouraged them to participate in her care. Today, Mangla is gradually reintegrating into her family, receiving both medical care and psychosocial support. Her recovery reflects what becomes possible when care enters the community, where it is no longer seen as something foreign or imposed, but as something that belongs.

At its heart, our work reaffirms a simple truth: healing begins where people feel seen, understood, and accompanied. Access, therefore, is not only about building services; it is about nurturing relationships of trust, compassion, and shared responsibility. As we continue this journey, we are reminded that communities hold immense wisdom and capacity for care.